Its been a while ago I started this series about measuring photo events with modern digital cameras used in astronomy. In my previous articles I provided a sketch of the light detection process in a modern CMOS camera, that is described by quantum efficiency qν and camera gain gPC. Also we shed light on camera gain gPC, that is the unity gain condition and discussed this situation with a typical DSLR camera. This monthly notice will focus on the Vega photometric system.

Its been a while ago I started this series about measuring photo events with modern digital cameras used in astronomy. In my previous articles I provided a sketch of the light detection process in a modern CMOS camera, that is described by quantum efficiency qν and camera gain gPC. Also we shed light on camera gain gPC, that is the unity gain condition and discussed this situation with a typical DSLR camera. This monthly notice will focus on the Vega photometric system.

Photometric systems

There are currently three major photometric systems in astronomy:

- ABν magnitude system

- STλ magnitude system

- Vega system, also referred as Johnson photometric system

The ABν magnitudes system (ABMag) is defined as a monochromatic flux constant in frequency, while the STλ magnitude system is defined as a monochromatic flux constant in wavelength. Both, the ABν and STλ systems, are artificial photometric systems defining different zeropoints for existing photometric filter systems. The Vega system or Johnson system historically is based on experimental measures, uses spectral flux density of real stars. Recent literature uses Vega as a prototype star and spectroscopic model to derive photometric calibration of photometric systems for any combination of filter system and detector, including the Johnson UBVRI system and Bessell's contributions to create a standard on this using different combinations and detectors that are closest to Johnsons original work. So, Vega is somehow connected to the Johnson UBV(RI) filter system. We will discuss the details about Vega later. However, don't confuse photometric systems with filter systems!

Apparent magnitude

The concept of apparent magnitude is the logarithm of the ratio of brightnesses of astronomical objects following Pogson's law. The difference in magnitude between two stars with fluxes ("brightness") f1 and f2 is given by:

mag = 2.5 log10 ( f1 / f2 )

A ratio of brightness will become a difference in magnitude. Two stars having fluxes (brightness) f1 and f2 with flux f2 dimmed by a factor of 100 compared to f1 the logarithm converts brightness factor into a magnitude difference of 5 mag. A difference of one mag between will yield a brightness ratio of approximately 2.512.

Throughout this article series, we follow general recommendations of journals and use the unit mag for magnitudes. If magnitudes refer to filter bands, this is indicated by letters in italic, like U, B, V, R or I in case of the Johnson-Cousins filter bands, for example. For narrow band filters it is sometimes practice to use the wavelength in nm or Angstrom, like mag5007 indicating magnitudes for an O-III narrowband filter centered at 500.7 nm. If no filter band is provided, assume to have visual apparent magnitudes, that are similar but not exactly the same, as the Johnson V band magnitude. While you may sometimes find the unit m instead of mag in astronomical literature, astronomical journals do not recommend the practice to use superscript m as the unit of magnitude.

Computations in mag are easier, the numbers more handy. Apparent magnitudes, i.e. the brightness the stars appear in the night sky, are of interest, as we want to describe the relationship between stellar magnitudes and fluxes measured. Don't confuse apparent magnitude with absolute magnitude, that is brightness as if the measurerd star would appear at a normalized distance of 10 parsec (for stars). If star f1 has apparent magnitude of 8.3 mag, then star f2 dimmed by a factor 100 in brightness will have magnitude 8.5+5=13.3 mag.

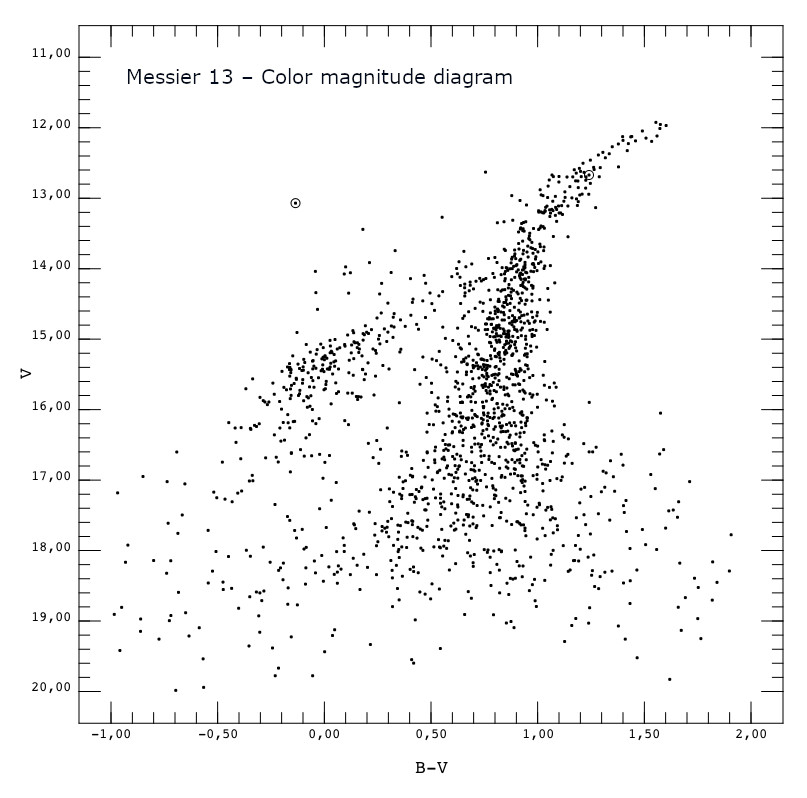

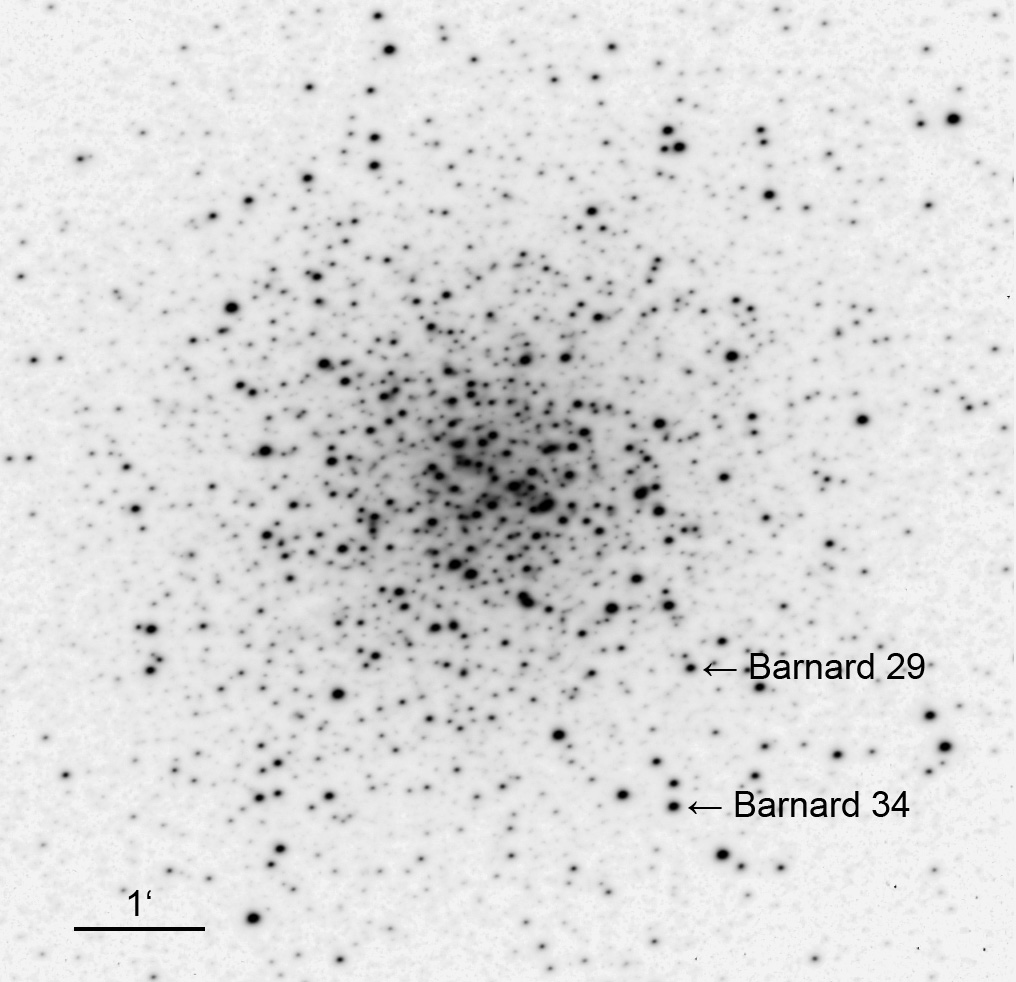

In stellar photometry a color index is the difference of two magnitudes measured in different passband color filters, like the Johnson B and V filter. Color indices are used as an indicator of spectral type and finally the type of a star, from its position in a plotted color magnitude diagram (CMD). Color indices, or simply colors of stars are important to derive astrophysical parameters, like age or total mass of a star cluster from a CMD.

Color-magnitude diagram B-V versus V derived from high-resolution imaging of Messier 13, taken with a 8" telescope and Canon DSLR.

The digital range of pixel intensities recorded by a DSLR spans 14 bit, or 16 bit with dedicated astronomical cameras. So the maximum span of mag from pixel intensities, that can be measured from a single exposure at 16 bit is limited to:

Δm = 2.5 log10 ( 65536 ) ≈ 12 mag.

A magnitude range of 12 mag sounds a lot. In fact, it does not reflect the possible large intensity range of stars in a star cluster or faint nebula feature. When trying to conduct precise photometry on stellar clusters down to the faint dwarfs, 12 mag is not enough to be covered by a single exposure. Depending on the flux of the bright night sky, camera bias, actual camera gain settings, and seeing effects mag range is more limited in practice. Keep in mind, when recording with high camera gain setting this will quickly reduce magnitude range in the digital image by cutting flux from brighter stars in the image. This is why it is not recommended to use high gain or ISO settings for advanced astrophotography.

Vega and the zeropoint of apparent magnitudes

Magnitudes express a ratio of fluxes (brightnesses) at logarithmic scale. Fortunately, apparent magnitudes got a zero point, that is zero. But the relationship between Vega (α Lyr) and the zeropoint of apparent magnitudes is complex. It is getting much more complex when looking at different filter systems. Vega is the brightest star in the Northern hemisphere and is of spectral type A0V. Historically and by definition Vega was chosen to define the zeropoint of apparent magnitude. Certain authors or lecturers simplify magnitudes and color indexes of Vega, in the Johnson UBV(RI) passbands, to be all zero. This is incorrect, however. Vega is not zeropoint of apparent magnitude for certain reasons. It also depends on the color filter and detector system used. In the original work of Johnson & Morgan (1953) about calibration of the Johnson UBV system, apparent magnitude and color indexes of Vega were provided as V=0.03, B-V=0.00 and U-B=0.01.

The magnitude of Vega has been reviewed and discussed many times for several reasons. Measures of different authors were compared, which yielded a magnitude of Vega found as V=0.03. Keep in mind: Johnson V refers to "visual" spectral range and wavelength. But spectral sensitiviy of any V filter plus detector is different from a human visual perception model at night. Visual observations are not in focus of precise astronomical measures, like stellar photometry. Measures in V passband are of importance, however. That's why Vega is not zeropoint, but "allowed" to have a non-zero magnitude when referring to any (arbitrary) filter detector and its calibration.

Slight variability of brightness is another issue with Vega. Variability of Vega is considered to be driven by dust clouds and oscillations of Vega. Sirius (α CMa) is also proposed as a reference when computing photometric systems and conversions. Stars of spectral type A0V are good candidates for calibration, because of interesting spectral properties. Sirius, a -1.5 mag star is another A0V star also considered as a reference for accurate calibration for spectral photometry. Due to limited observability it is not a good reference from Northern hemisphere, however. There are a number of catalogs for reference stars for calibration and also white dwarfs have been considered.

Conclusion and outlook

Magnitudes are connected to fluxes by Pogson's law. Apparent magnitude is a measure of brightness (flux) expressed at logarithmic scale. To summarize, Vega's apparent magnitude in Johnson UBV passband filters is not exactly zero. Magnitude in Johnson V passband shall be assumed as V=0.03, which is a deviation of 2.8% (percent) from zero. Vega will define an actual zeropoint of UBV magnitudes, but doesn't have brightness V=0.00.

Of more importance is: The fundamental property of the concept of apparent magnitude, its zeropoint offers the opportunity to derive apparent magnitude from photon count measures. The zeropoint defines a reference brightness used to compare apparent magnitude to the reference from where we may build the relationship between apparent magnitude and photon count. The reference could be approximately Vega and many other well known reference stars suited to derive magnitudes. For more details, see the work of Johnson & Morgan (1953), Bessel (2005) or Stritzinger (2005).

For further discussions we may ignore the minor differences of values discussed between different authors and also Vega's variability. Vega certainly must be regarded as one of many zeropoint reference stars for calibration. The Vega system is still of importance in spectrophotometry, also because spectral fluxes in different passbands may use Vega spectrum for flux calibration in various filter bands. This is also because Vega is bright to provide a good signal. This will be covered by the next article.

Stay tuned! To be continued soon...

Literature

- Apparent magnitude, Wikipedia

- SI units in astronomy, IAU archive at the European Southern Observatory

- Johnson, H. L. ; Morgan, 1953. Fundamental stellar photometry for standards of spectral type on the Revised System of the Yerkes Spectral Atlas

- Gray, R. O., 2007. The problems with Vega. The Future of Photometric, Spectrophotometric and Polarimetric Standardization, ASP Conference Series, Vol. 364, 2007., p.305

- Butkovskaya, V. V., 2014. On the variability of Vega. Bulletin of the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, Volume 110, Issue 1, pp.80-84

- Bessell, M. S., 2005. Standard Photometric Systems. Ann. Rev. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 43, 1, pp.293-336

- Stritzinger et al., 2005. An Atlas of Spectrophotometric Landolt Standard Stars. PASP, 117, 834, pp. 810-822.

- Rieke et al., 2022. Infrared Absolute Calibration. I. Comparison of Sirius with Fainter Calibration Stars. The Astronomical Journal, 163, 2, 45, 15 pp.